Things Hidden Since the Foundation of the Algorithm

Create for creations sake or risk total destruction

What impoverishes the ego is the very desire to be that ego — the desire for the kind of narcissism that is never ours but can be seen radiating from the other to whom we enslave ourselves. - René Girard

A gnawing inadequacy emerges after scrolling through Instagram. We feel an inexplicable resentment toward people we barely know, and shame when we compare our mundane reality to someone else’s curated highlights. Countless essays have diagnosed social media’s corrosive effects on self-confidence and its cultivation of endless desire. They describe the symptoms without exposing the underlying disease.

René Girard went further. In “Things Hidden Since the Foundation of the World,” he unveiled the precise psychological mechanism that transforms innocent observation into toxic comparison, admiration into resentment, and aspiration into self-defeating despair. His theory of mimetic desire reveals an ancient pattern in human psychology that the algorithm has perfected.

If any ideas deserve serious examination today, it is these. Girard’s insights expose how desire itself operates, how it spreads through communities like contagion, and why our digital age has become a pressure cooker for the very forces that have driven human conflict since the beginning of civilization.

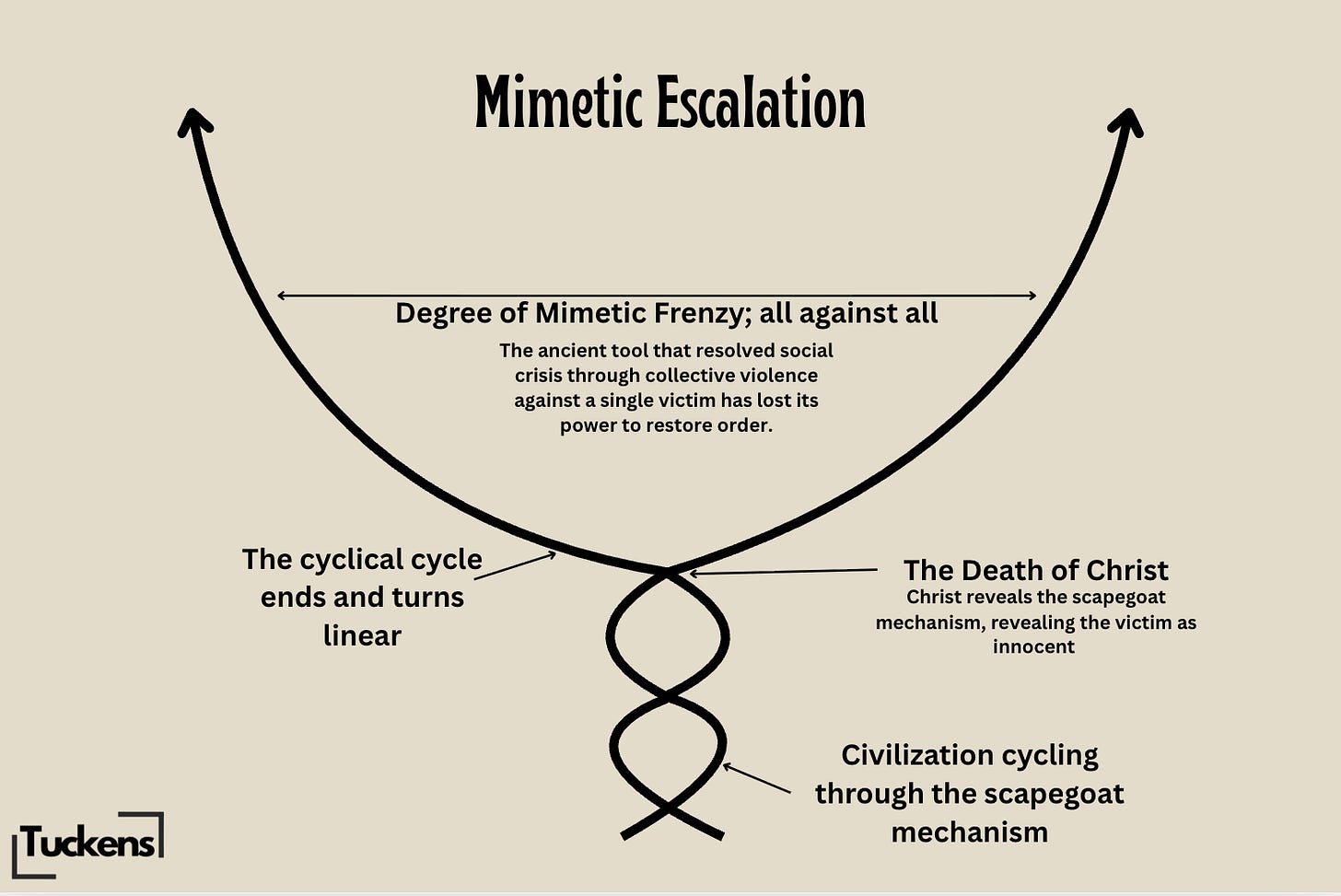

The first realization is that the world is becoming more undifferentiated and interconnected, dismantling the very structures that once contained mimetic rivalry. With each passing day, the barriers that historically protected us from mimetic frenzy are torn down. Geographic distance no longer separates us from potential models; we now compare ourselves not to our neighbors but to billions of strangers across the globe. Cultural distinctions that once created clear boundaries of identity and aspiration dissolve in multi-ethnic cities where everyone competes on the same terms. Professional hierarchies flatten as social media collapses the protective distance between entry-level workers and executives, students and experts, amateurs and celebrities. The result is mimetic rivalries that scale across the world.

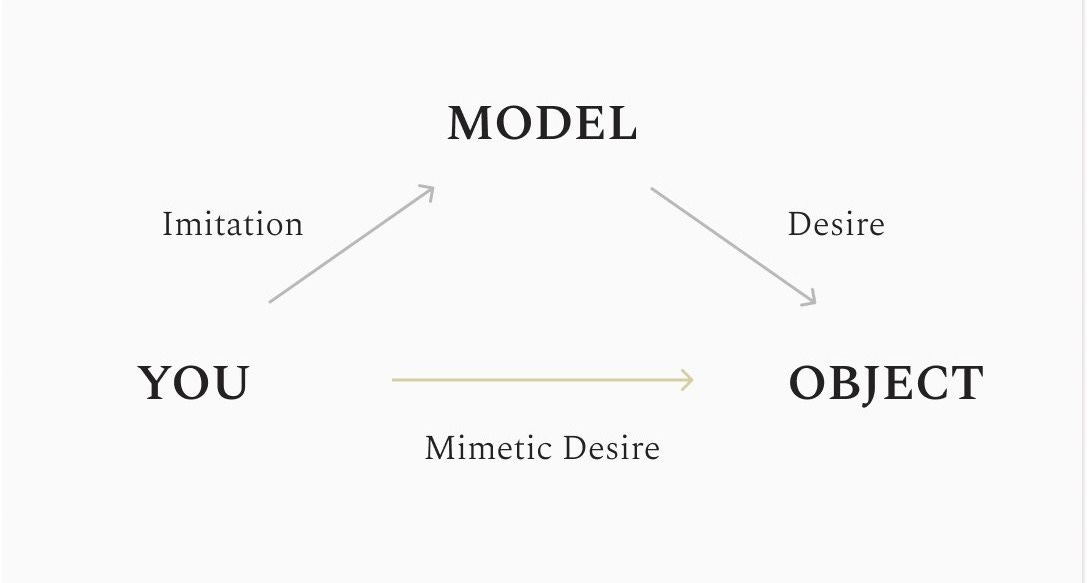

Soon, there will be nothing to stop an American from competing with a Singaporean or even a Seychellean: our mimetic desires, the wants we catch from watching others want things, now operate at a global scale, unbound by geography. Any post of a yacht doesn’t show me an object, but it reveals a model of desire whose very act of possessing triggers my own wanting. The image induces shame because I recognize myself as lacking what my mediator, the person who shows me what to desire, effortlessly displays.

Multiply that experience by 100x a day, and you have a person who lives in constant angst, trapped in an accelerating cycle of mimetic rivalry where every scroll deepens the wound. Everything we see, every person we come across, we observe not as themselves but as rivals in a war of all against all: each encounter is a potential site of mimetic competition where their being becomes an obstacle to our own. We are caught in what Girard called the double bind; we must imitate our models to learn what to desire, yet that very imitation transforms them into obstacles we must overcome, fueling resentment and the metaphysical desire to possess not just what they have, but their very being.

The hidden belief driving this cycle… “If I had what they have, I would be what they are.”

How the Algorithm Abuses Metaphysical Desire

The algorithm is the first technology perfectly calibrated to exploit metaphysical desire because it solves the mediator scarcity problem. For the majority of humanity’s time on Earth, mediators have been scarce, and more importantly, they were differentiated from the common citizen. The algorithm bypasses this natural order of things by overwhelming the user with a plethora of mediators that the subject then uses as proxies for desire. The effect would be mitigated if the subject had a confined idea of his place in society or what he is capable of accomplishing/representing.

Instead, especially in America, from youth, we are taught that we can do anything, we can become anyone. This school of thought feeds directly into the fires of mimetic desire. We are conditioned to believe that we are more than we are, that our natural place in the world is only a suggestion, that we have the freedom to rise above our current condition, and that we deserve to be more. The desire to become is animated by our limitless potential, pushing us to reach far beyond our capacity. We have dreams of grandeur, and instead of society putting those dreams in their proper place, it spurs the desire for more, to consume more, to be more.

What society fails to reveal is where desire spawns from. When we desire something, we think that the desire is our own. Instead, what I am arguing is that our desires are not our own, but that we accumulate our desires from models, that our model then mediates our desire for the object. The result is that we do not really desire the object, but what we desire is the model's very being, its sense of autonomy and freedom. This becomes metaphysical desire: the longing not for any particular possession but for the model's apparent completeness, their freedom from lack itself. We want to inhabit their state of being, to possess the self-sufficiency we imagine they have achieved.

Consider the young professional who buys the luxury watch. They tell themselves they want the craftsmanship, the design, the way it catches light. But trace the desire backward, and you find the senior partner who wears one, who seems to move through the world with effortless confidence, whose time appears to be entirely their own. The watch is merely the visible marker of a way of being: the freedom, the arrival, the sense of having made it. What's really desired isn't the object on the wrist but the existential position it seems to signify: the end of striving, the achievement of self-sufficiency, the state of no longer needing to want.

The algorithm has learned to feed us an endless stream of models, each one calibrated to our demonstrated interests and desires, each one pulling us deeper into mimetic frenzy. Our desires multiply, with each model adding on a new tier of desires. Instead of energizing us, this process demoralizes our inclination to be by causing us shame. This shame then turns into resentment; we no longer see the model as a kind of mentor, but as an obstacle, an enemy who is stopping us from reaching metaphysical autonomy. Our resentment for these models grows, with each passing scroll, we get farther from possessing the object of our desire.

What makes the algorithm so psychologically insidious is that it enables the inflation of desirable objects, amplifying their perceived value far beyond their actual worth. Through carefully curated content, the model can signal experiences, achievements, and virtues that they do not genuinely possess or that represent only exceptional moments rather than everyday reality. This creates a profound sense of inadequacy in the subject, who compares their unfiltered life against the model’s highlight reel and becomes increasingly ashamed of what they perceive as their inferior existence.

Consider a teenager scrolling through Instagram: they see their peer (the model) posting photos from exotic vacations, perfect relationships, and glamorous parties. Each post suggests a life of constant excitement and fulfillment. What remains invisible are the ordinary hours, the conflicts, the staged nature of each shot. The subject, meanwhile, experiences their own life in full resolution: the boredom, the rejections, the mundane afternoons. This asymmetry of perception inflates the gap between them.

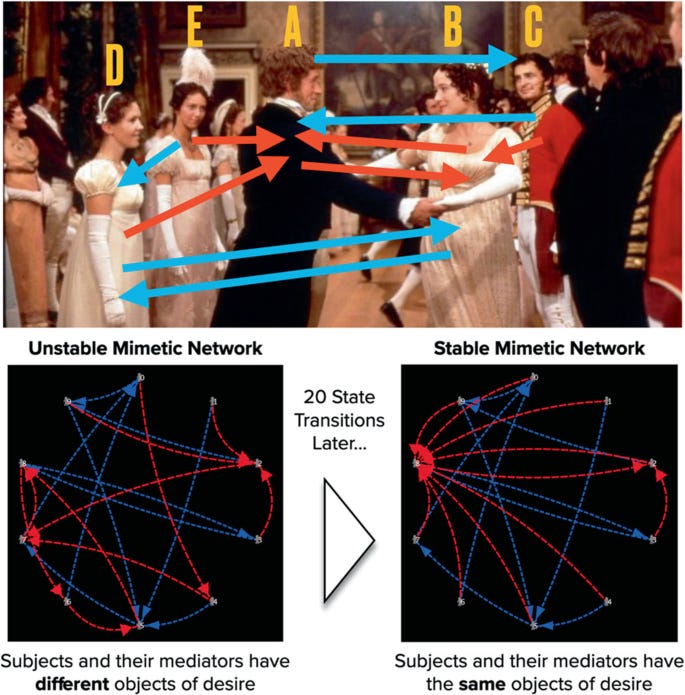

The algorithmic amplification of these false identities deepens the ontological chasm, the perceived difference in level of being, between subject and model. As more people simultaneously occupy both roles (being models to some while serving as subjects to others), the mimetic network becomes increasingly unstable. Everyone is performing a curated identity while feeling inadequate compared to others’ performances. This recursive pattern of imitation and aspiration ultimately escalates into what René Girard called mimetic frenzy1: a collective crisis where desire becomes so entangled and frustrated that the social fabric itself begins to destabilize.

The Model You’ll Never Surpass

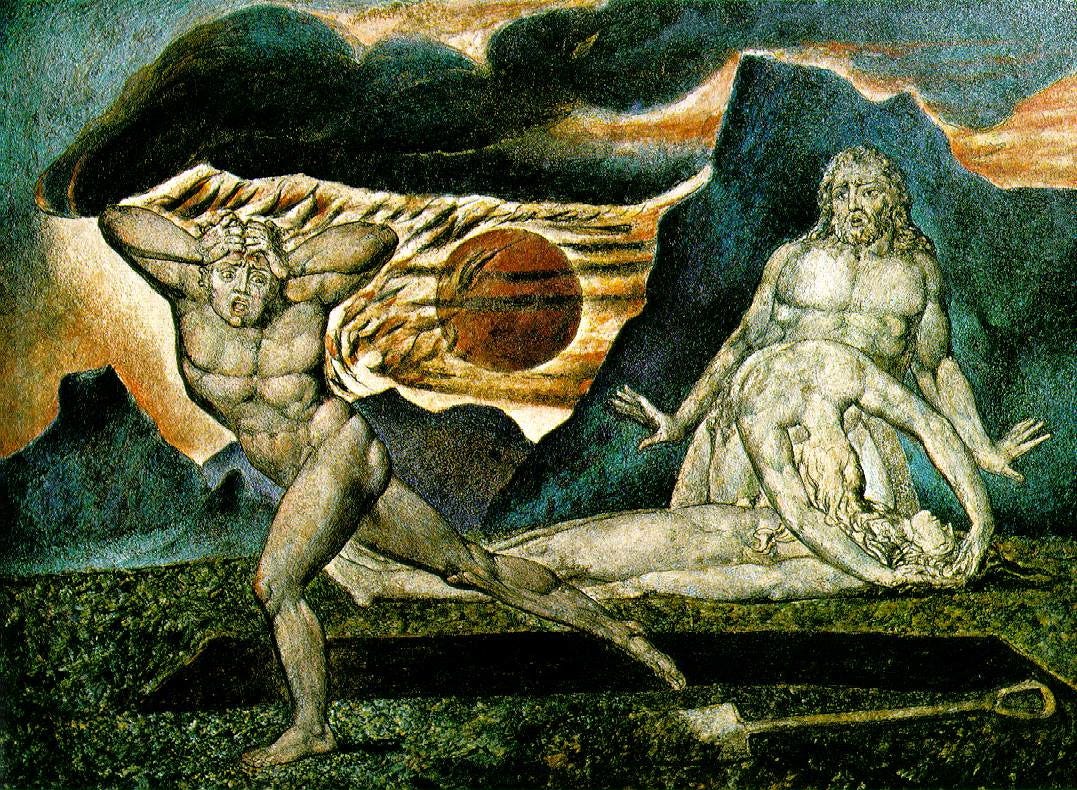

When the model of desire is close to us, similar to us, and competing for the same goods, desire escalates into rivalry, resentment, and eventually violence. Modern egalitarian societies intensify this by erasing the distance between people while multiplying models. In order to exit mimetic rivalry, we must transform our competitive desires into non-competitive desires, modeled on Christ. Girard’s solution is very clear; we must renounce violence, renounce zero-sum games, and refuse to be the model that is imitated.

There are two kinds of models: rivalrous models, who are people that compete with you, and transcendent models, who are figures that cannot become your rivals. Christ is Girard's central example of a transcendent model because he desires nothing that deprives others, refuses retaliation, exposes scapegoating rather than participating in it2, and his imitation multiplies peace rather than rivalry. This is why Girard calls Christianity the only true anti-mimetic solution3, even though it works by imitation.

What we need is “desire literacy,” the ability to catch the moment wanting is being installed. Mimetic desire is so ingrained in the human psyche that it cannot be fully gotten rid of. It is a condition that we have to learn to deal with, and can temper through a kind of desire conversion. We can do this by choosing humility over recognition, truth over winning, love over reciprocity, forgiveness over revenge. This positioning at first comes off as weak, but in the end, it is the only solution to a world escalating towards total destruction.

If we anchor our being in something that we cannot compete with, then we do not experience the same rivolrous traits that arise from competition.

This is why Paul says in 2 Corinthians 10:12

Not that we dare to classify or compare ourselves with some of those who are commending themselves. But when they measure themselves by one another and compare themselves with one another, they are without understanding.

And Christ in John 5:41

I do not receive glory from people.

Paul says in Galatians 1:10

For am I now seeking the approval of man, or of God? If I were still trying to please man, I would not be a servant of Christ.

The common theme here is the positioning of mimesis on a model that can never be a rival: God or Jesus. This transcendent model fundamentally transforms the nature of desire itself. While the act of seeking approval from God rather than from man might appear to be a withdrawal from the world, a kind of retreat into private spirituality, it actually produces the opposite effect. What happens is that the individual is no longer dependent on the world to verify his existence or validate his worth.

By orienting desire toward a non-rivalrous model, the individual escapes the endless cycle of comparison and competition that characterizes human relationships. He is thus freed from mimetic contagion, able to engage with others without the constant undercurrent of envy, resentment, or the need to prove himself superior. This freedom paradoxically allows for more authentic engagement with the world, not less, because the individual can now act from a place of secure identity rather than anxious striving.

Conclusion

Ultimately, Girard’s mimetic theory reveals why comparison corrupts judgment: when we measure ourselves against rivals, we lose sight of truth itself, subordinating it to the endless pursuit of recognition. What begins as innocent observation quickly devolves into a zero-sum calculus where truth becomes irrelevant and winning becomes everything. We no longer ask “Is this valuable?” but rather “Does possessing this elevate me above my rivals?” The tragedy is that rivalry is structurally endless. Each victory only produces new competitors, each achievement merely shifts the terms of comparison. The teenager who finally gets the perfect Instagram post discovers that perfection is a moving target; the professional who reaches the executive suite finds new hierarchies to climb. There is no summit because the mountain itself is generated by mimetic desire, growing taller with each step we take.

One practical escape from this cycle lies in shifting from consumption to creation. Creation undertaken for its own sake and not for recognition. The algorithm trains us to be passive spectators, accumulating shame with each scroll. Creating without regard for applause offers a different relationship to desire entirely. When we write not to be read but to think clearly, when we build not to impress but to solve problems, we exit the mimetic marketplace. This kind of creation is non-rivalrous because it doesn’t depend on defeating others or claiming scarce status. A musician who plays for the love of music cannot be your rival in the way an influencer competing for followers can. The act itself becomes the reward, not a means to metaphysical autonomy borrowed from models.

Peace, therefore, requires something more radical than winning the competitive game: it requires anchoring identity outside the competitive field entirely. This is the profound insight behind Girard’s elevation of Christ as the transcendent model: imitation must be non-rivalrous, or it inevitably becomes violent. A model who desires nothing that deprives others, who refuses retaliation, who exposes rather than perpetuates scapegoating: such a model cannot trigger the mimetic spiral. By orienting our desires toward a model who cannot be our rival, we escape mimetic contagion without abandoning imitation itself. We remain social creatures who learn through imitation, but we imitate peace rather than rivalry, humility rather than pride, truth rather than recognition. The question Girard leaves us with is not whether we will imitate (that is inevitable) but whom we will imitate, and whether that imitation will multiply peace or perpetuate conflict.

The journey towards a unified world starts from within.

Thank you for reading.

May your eyes be bright and full of everlasting laughter.

René Girard, Things Hidden Since the Foundation of the World (orig. French 1978; English trans. Stephen Bann and Michael Metteer, Stanford University Press, 1987), p. 26.

Girard, René. The Scapegoat. Translated by Yvonne Freccero. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1989.

Girard’s core claim is basically this:

Human culture and myth are structured by violence (the scapegoat mechanism sitting underneath them).

Christ uniquely stands outside that violent logic, and therefore can “unmask” it and break its grip.

So, to confess Christ as God is, for Girard, to recognize him as the one who can rise above the violence that previously “transcended” humanity and free us from those structures.

“the only being capable of rising above the violence that had … absolutely transcended mankind.”

Girard, René, Jean-Michel Oughourlian, and Guy Lefort. Things Hidden Since the Foundation of the World. Translated by Stephen Bann and Michael Metteer. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 1987. Book II, Chapter 2 (“A Non-Sacrificial Reading of the Gospel Text”), section “The Divinity of Christ,” p. 219.

Very profound and thought-provoking! Love the concept of peace through creating for purposes other than competition.